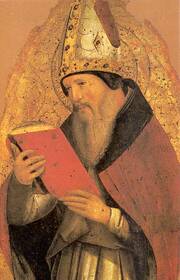

Saint Augustine of Hippo

Philosophy & Faith with Father Francis Selman ♦

More on St Augustine (including Pope Benedict XVI's catecheses) here

"Although St Augustine belongs to the end of the ancient world (he was born in AD 354 and died in 430 as the Vandals were overrunning Northern Africa, where he was Bishop of Hippo), he was also a surprisingly modern man in some respects. He gave us, for example, the first psychological autobiography ever written, his famous Confessions. In this book, he tells us that as a young man he was attracted by the philosophy of Plato. He also lived with a mistress, but his mother St Monica, persuaded him to give up his mistress so that he could pursue a proper career. So he sailed to Italy to become an orator, but he was disillusioned in Rome and moved to Milan. Here he met St Ambrose. The result was that he became a Christian, baptised in the year 387. Within a few years he gave up his academic life, became a priest and Bishop of Hippo in 395. In the middle of his pastoral cares, he wrote two great books: The City of God, which gives us a philosophy of history, and the De Trinitate (On the Trinity), where we find his philosophy of mind. In this talk I want to consider just briefly 3 topics in his philosophy: they are words, memory and the soul. St Augustine possessed a wonderful capacity for exploring the mind: when it is one’s own mind that one is exploring, we do this by introspection, looking within ourselves. Thus Augustine is the master of what might be called “innerliness”. But what Augustine found in himself was not so much himself as God.

Naturally, as an orator, Augustine had an interest in words. In an early work On the Teacher (De Magistro), he asked the question, What does the teacher teach a pupil? In other words, what does someone learn from the teacher when he teaches? For example, what do I learn from someone who teaches me the meaning of a word? Do I just learn the meaning of a word? Does a word just signify an idea or meaning which is as though the object that the word names? Or does a word signify and refer to a reality? We are taught the meanings of words and what things are called when we are children, for example, when we learnt the names of colours. What is orange? That is orange (a colour, or a piece of fruit that is a real object). The word “river” obviously names a real thing or object. But what reality does the phrase “no river” name? I just mention these few examples, because we are using words all the time in communicating but we rarely reflect on the nature of words. St Augustine saw that words are signs. The word “word” is itself a sign of something. St Augustine was the first to think of sacraments as signs of inner realities. Not all words are signs of things: some are the logical constants and connecting words, like “and”, “but”, “although”.

But how do I know that what the teacher is telling me is the true meaning of a word? Here, St Augustine says that the teacher does not really teach me anything; rather he reminds me of realities that I already know. And how am I already to know these realities, real things? Because God illumines my mind. When the teacher tells me something, I consult the truth that is within me, St Augustine says, to see that what the teacher says is true. Our real teacher is Christ, the one who teaches within, our interior teacher. Once Augustine had become a Christian he could no longer hold that our souls pre-exist, as Plato believed. So he had to find some other way that we know ideas. He said it was by divine illumination. Aristotle had said that we have to make our ideas (we are not already born with them, as Plato thought), but Augustine said that God puts the ideas in us. This theory of ideas later influences Descartes, the Father of Modern Philosophy.

We now come to memory. Augustine wrote a wonderful section on memory in Book 10 of the Confessions. Augustine is searching for God. He searches throughout the universe, from the fish at the bottom of the sea to the stars in the furthest heavens, but each thing that he asks in turn replies “We did not make ourselves, seek higher”. In the end Augustine realises that God is not to be found in the things outside him, so he turns within himself. His reflections on memory are part of his search for God. Augustine thought that we would not seek God unless we had some memory of him and therefore some memory of God had remained in mankind after the Fall, which was transmitted from Adam. He saw evidence of this in the fact that everyone seeks happiness (remember that happiness was the purpose of philosophy for Plato and the end of life for Aristotle), but we would not seek happiness unless some original memory of it remained in us. He observes that everyone likes to think that their happiness is founded in truth: no-one wants his or her happiness to be shown to be false.

We find many things in our memory: historical dates, theorems of mathematics, etc.. Memory was like a great treasure house in Augustine’s view. One of the things we find in memory is ourselves. This is to be conscious of ourselves, when we do not forget ourselves. Thus memory came to have as second meaning in Augustine, of self-consciousness. When I am conscious of things outside me, they are present to me. When I am conscious of myself I am present to myself. Nothing is more present to the mind, Augustine remarked, than the mind itself. Thus the mind knows itself.

What did Augustine think that the mind knows about itself? That it is not material like the body, but immaterial. Here I think that St Augustine gives two good reasons which retain all their relevance for today. First, as the mind knows it is distinct from the material things it thinks about, if it were air or fire, as some of the ancients thought, it would think of air or fire in another way than it does about other matter, and so not with an imaginary fantasy. But we do not think of air or fire in another way, so the mind does not consist of anything material: it is immaterial. Second, the mind does not have parts like a body: it is not extended like material bodies. Here we find the origin of Descartes’ distinction of the universe into extended and thinking substances. The mind consists of memory, understanding and will, but these are not three parts of the mind. The mind is all three of these indivisibly. Thus St Augustine could use the mind as an analogy for the Holy Trinity, the Father, Son and Holy Spirit are each God but there is only one God, not three, just as the mind is wholly memory, understanding and will. The connection between the understanding and memory is the will. The will directs the mind to the memory, where images are stored, and also directs the attention of the mind to its objects of thought. We don’t look outside ourselves to the Ideas and Forms as Plato did but turn inwards to the memory."