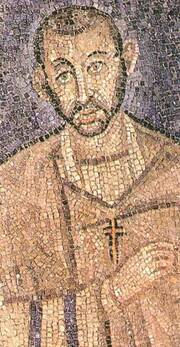

Saint Ambrose of Milan

Bishop & Doctor of the Church

Born c 339 AD in Augusta Treverorum, Gallia Belgica, Roman Empire (present-day Germany)

Died on 4 April 397 in Mediolanum, Italia annonaria, Roman Empire (present-day Italy)

Shrine: Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio, Milano

Feast day - 7th December (he was consecrated bishop on 7 December 374)

Pope St John Paul II gave us his encyclical Redemptoris Missio on the Feast of St Ambrose 1990.

St Ambrose: "Omnia Christus est nobis! If you have a wound to heal, he is the doctor; if you are parched by fever, he is the spring; if you are oppressed by injustice, he is justice; if you are in need of help, he is strength; if you fear death, he is life; if you desire Heaven, he is the way; if you are in the darkness, he is light.... Taste and see how good is the Lord: blessed is the man who hopes in him!"

3 2us by Father Emmanuel Mansford CFR ![]()

"This man, this bishop, this shepherd, clearly in his life was reproduced the life of Christ. I think in our times when there's increasingly greater confrontation between the Church and the secular authorities of civil society, that we need the courage of St Ambrose and we need shepherds who have his gift of prayer and humility and fortitude to stand firm. And if we look at how God chose him, it's a reminder to all of us that we never know what God has in store for us, but once we submit to His plan, simply to put ourselves into the hands of God, and to allow His grace but also the gifts that He has given us to be used for his glory. So, Saint Ambrose, pray for us."

Catechesis by Papa Benedict XVI

General Audience, Wednesday 24 October 2007 - in Croatian, English, French, German, Italian, Portuguese & Spanish

"Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Holy Bishop Ambrose died in Milan in the night between 3rd and 4th April 397. It was dawn on Holy Saturday. The day before, at about 5 o'clock in the afternoon, he had settled down to pray, lying on his bed with his arms wide open in the form of a cross. Thus, he took part in the solemn Easter Triduum, in the death and Resurrection of the Lord. "We saw his lips moving", said Paulinus, the faithful deacon who wrote his Life at St Augustine's suggestion, "but we could not hear his voice". The situation suddenly became dramatic. Honoratus, Bishop of Vercelli, who was assisting Ambrose and was sleeping on the upper floor, was awoken by a voice saying again and again, "Get up quickly! Ambrose is dying...". "Honoratus hurried downstairs", Paulinus continues, "and offered the Saint the Body of the Lord. As soon as he had received and swallowed it, Ambrose gave up his spirit, taking the good Viaticum with him. His soul, thus refreshed by the virtue of that food, now enjoys the company of Angels" (Life, 47). On that Holy Friday 397, the wide open arms of the dying Ambrose expressed his mystical participation in the death and Resurrection of the Lord. This was his last catechesis: in the silence of the words, he continued to speak with the witness of his life.

Ambrose was not old when he died. He had not even reached the age of 60, since he was born in about 340 AD in Treves, where his father was Prefect of the Gauls. His family was Christian. Upon his father's death while he was still a boy, his mother took him to Rome and educated him for a civil career, assuring him a sound instruction in rhetoric and jurisprudence. In about 370 he was sent to govern the Provinces of Emilia and Liguria, with headquarters in Milan. It was precisely there that the struggle between orthodox and Arians was raging and became particularly heated after the death of the Arian Bishop Auxentius. Ambrose intervened to pacify the members of the two opposing factions; his authority was such that although he was merely a catechumen, the people acclaimed him Bishop of Milan.

Until that moment, Ambrose had been the most senior magistrate of the Empire in northern Italy. Culturally well-educated but at the same time ignorant of the Scriptures, the new Bishop briskly began to study them. From the works of Origen, the indisputable master of the "Alexandrian School", he learned to know and to comment on the Bible. Thus, Ambrose transferred to the Latin environment the meditation on the Scriptures which Origen had begun, introducing in the West the practice of lectio divina. The method of lectio served to guide all of Ambrose's preaching and writings, which stemmed precisely from prayerful listening to the Word of God. The famous introduction of an Ambrosian catechesis shows clearly how the holy Bishop applied the Old Testament to Christian life: "Every day, when we were reading about the lives of the Patriarchs and the maxims of the Proverbs, we addressed morality", the Bishop of Milan said to his catechumens and neophytes, "so that formed and instructed by them you may become accustomed to taking the path of the Fathers and to following the route of obedience to the divine precepts" (On the Mysteries 1, 1). In other words, the neophytes and catechumens, in accordance with the Bishop's decision, after having learned the art of a well-ordered life, could henceforth consider themselves prepared for Christ's great mysteries. Thus, Ambrose's preaching - which constitutes the structural nucleus of his immense literary opus - starts with the reading of the Sacred Books ("the Patriarchs" or the historical Books and "Proverbs", or in other words, the Wisdom Books) in order to live in conformity with divine Revelation.

It is obvious that the preacher's personal testimony and the level of exemplarity of the Christian community condition the effectiveness of the preaching. In this perspective, a passage from St Augustine's Confessions is relevant. He had come to Milan as a teacher of rhetoric; he was a sceptic and not Christian. He was seeking the Christian truth but was not capable of truly finding it.

What moved the heart of the young African rhetorician, sceptic and downhearted, and what impelled him to definitive conversion was not above all Ambrose's splendid homilies (although he deeply appreciated them). It was rather the testimony of the Bishop and his Milanese Church that prayed and sang as one intact body. It was a Church that could resist the tyrannical ploys of the Emperor and his mother, who in early 386 again demanded a church building for the Arians' celebrations. In the building that was to be requisitioned, Augustine relates, "the devout people watched, ready to die with their Bishop". This testimony of the Confessions is precious because it points out that something was moving in Augustine, who continues: "We too, although spiritually tepid, shared in the excitement of the whole people" (Confessions 9, 7).

Augustine learned from the life and example of Bishop Ambrose to believe and to preach. We can refer to a famous sermon of the African, which centuries later merited citation in the conciliar Constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum: "Therefore, all clerics, particularly priests of Christ and others who, as deacons or catechists, are officially engaged in the ministry of the Word", Dei Verbum recommends, "should immerse themselves in the Scriptures by constant sacred reading and diligent study. For it must not happen that anyone becomes" - and this is Augustine's citation - ""an empty preacher of the Word of God to others, not being a hearer of the Word in his own heart'" (n. 25). Augustine had learned precisely from Ambrose how to "hear in his own heart" this perseverance in reading Sacred Scripture with a prayerful approach, so as truly to absorb and assimilate the Word of God in one's heart.

Dear brothers and sisters, I would like further to propose to you a sort of "patristic icon", which, interpreted in the light of what we have said, effectively represents "the heart" of Ambrosian doctrine. In the 6th book of the Confessions, Augustine tells of his meeting with Ambrose, an encounter that was indisputably of great importance in the history of the Church. He writes in his text that whenever he went to see the Bishop of Milan, he would regularly find him taken up with catervae of people full of problems for whose needs he did his utmost. There was always a long queue waiting to talk to Ambrose, seeking in him consolation and hope. When Ambrose was not with them, with the people (and this happened for the space of the briefest of moments), he was either restoring his body with the necessary food or nourishing his spirit with reading. Here Augustine marvels because Ambrose read the Scriptures with his mouth shut, only with his eyes. Indeed, in the early Christian centuries reading was conceived of strictly for proclamation, and reading aloud also facilitated the reader's understanding. That Ambrose could scan the pages with his eyes alone suggested to the admiring Augustine a rare ability for reading and familiarity with the Scriptures. Well, in that "reading under one's breath", where the heart is committed to achieving knowledge of the Word of God - this is the "icon" to which we are referring -, one can glimpse the method of Ambrosian catechesis; it is Scripture itself, intimately assimilated, which suggests the content to proclaim that will lead to the conversion of hearts.

Thus, with regard to the magisterium of Ambrose and of Augustine, catechesis is inseparable from witness of life. What I wrote on the theologian in the Introduction to Christianity might also be useful to the catechist. An educator in the faith cannot risk appearing like a sort of clown who recites a part "by profession". Rather - to use an image dear to Origen, a writer who was particularly appreciated by Ambrose -, he must be like the beloved disciple who rested his head against his Master's heart and there learned the way to think, speak and act. The true disciple is ultimately the one whose proclamation of the Gospel is the most credible and effective.

Like the Apostle John, Bishop Ambrose - who never tired of saying: "Omnia Christus est nobis! To us Christ is all!" - continues to be a genuine witness of the Lord. Let us thus conclude our Catechesis with his same words, full of love for Jesus: "Omnia Christus est nobis! If you have a wound to heal, he is the doctor; if you are parched by fever, he is the spring; if you are oppressed by injustice, he is justice; if you are in need of help, he is strength; if you fear death, he is life; if you desire Heaven, he is the way; if you are in the darkness, he is light.... Taste and see how good is the Lord: blessed is the man who hopes in him!" (De Virginitate, 16, 99). Let us also hope in Christ. We shall thus be blessed and shall live in peace."

Commentary by St Ambrose on Saint Luke's gospel (VII, 176-180) - The mustard seed

Now let us see why the Kingdom of Heaven is compared to a mustard seed. Another passage that refers to a mustard seed comes to mind where it is compared to faith, when the Lord says: «If you had faith like a mustard seed you would say to this mountain: «Cast yourself into the sea» ((cf. Mt 17,20; Mk 11,23)... So if the Kingdom of heaven is like a mustard seed and faith is like a mustard seed, then it goes without saying that faith is the Kingdom of heaven and the Kingdom of heaven is faith. To possess faith is to possess the Kingdom... That is why Peter, whose faith was genuine, was given the keys of the Kingdom of heaven that he might likewise open it up to others (Mt 16,19).

Next, let us appreciate what the gist of this comparison is. Without any doubt this seed is something perfectly ordinary and uncomplicated. But only cook it and it exudes its strength. In the same way, faith seems something simple at first glance, but when crushed by adversity, its strength increases... Our martyrs Felix, Nabor and Victor were like mustard seeds: although they bore the odor of faith, yet they were passed over. But when persecution came, they laid down their weapons, extended their necks and, struck by the sword, shed abroad the beauty of their martyrdom «even to the ends of the earth» (Ps 19[18],5)...

But our Lord himself is a mustard seed: so long as he had undergone no attack, the people did not recognise him. He chose to be hustled...; he chose to be pressed in such a way that Peter said: «The crowds are pressing in upon you» (Lk 8,45); he chose to be sown like a seed «that a man takes and throws on his garden», for it was in a garden that Christ was both arrested and buried. He grew up in this garden and was even raised up again in it... You, too, sow Christ in your gardens, then... Sow the Lord Jesus: he was seed when he was arrested, tree when he rose again – a tree overshadowing the world. He was seed when buried in the earth, tree when he rose up to heaven.

Commentary by St Ambrose on St Luke's Gospel, 7, 45.59

As he sent out disciples into his harvest - which had,in truth,been sown by the Father's Word but which required to be worked over, cultivated and carefully tended if the birds were not to ravage the seed - Jesus said to them: “Behold, I send you out like lambs among wolves”... The Good Shepherd could not but fear wolves in his flock: these disciples were sent to spread grace abroad, not to become a prey. But the Good Shepherd's care prevented the wolves from doing anything against the lambs he sends out. He sends them that Isaiah's prophecy might be fulfilled: “The wolf and the lamb shall graze alike” (Is 65,25)... And besides, were not the disciples who were sent out ordered not even to carry a staff?...

What our humble Lord laid down, his disciples also accomplished by practising humility. For he sends them out to broadcast the faith, not by force but by their teaching; not by exerting force of will but by exalting the doctrine of humility. And he thought good to link patience to humility since, according to Peter's testimony: “When he was insulted, he returned no insult; when he suffered, he did not threaten” (1Pt 2,23).

This amounts to saying: “Be imitators of me: let go of your thirst for revenge; respond to the blows of pride, not by returning evil for evil but with the patience that forgives. No one should perform on their own account what they reprehend in others; gentleness confronts the arrogant with far greater strength”.